I Take Much Pride To Introduce To You One Of The Pioneers In Temple Construction Company, Our Company “JAYDEEP STONE ART “Have Been In The Business Of Temple Construction and planning For More Than A Decade Now And Still Counting.

Our Company Has Already Built Many Temple With Art Of Shilp Shastra In Whole India, Our Service Include Contracting Service And We Are Also Into The Business Of Building Construction, It’s Our Goal To Constructs Temple With All Rule Of Shilp Shastra, Thus We Use Shilp Shastra Technology And Design Is One Of Our Concerns. All of Our Service Are Safe Because We Are Registered Firm.

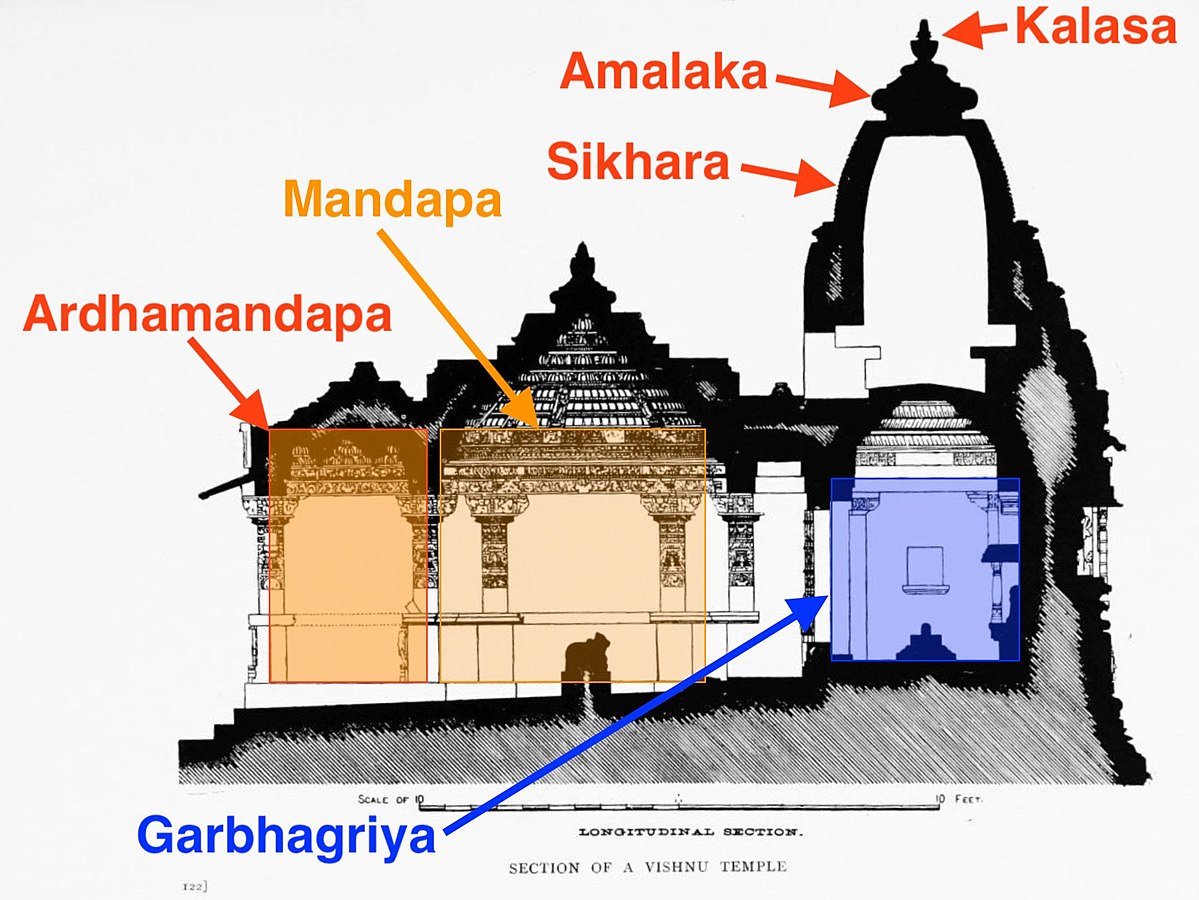

Hindu temple architecture as the main form of Hindu architecture has many varieties of style, though the basic nature of the Hindu temple remains the same, with the essential feature an inner sanctum, the garbha griha or womb-chamber, where the primary Murti or the image of a deity is housed in a simple bare cell. Around this chamber there are often other structures and buildings, in the largest cases covering several acres. On the exterior, the garbhagriha is crowned by a tower-like shikhara, also called the vimana in the south. The shrine building often includes an circumambulatory passage for parikrama, a mandapa congregation hall, and sometimes an antarala antechamber and porch between garbhagriha and mandapa. There may further mandapas or other buildings, connected or detached, in large temples, together with other small temples in the compound

Hindu temple architecture reflects a synthesis of arts, the ideals of dharma, beliefs, values and the way of life cherished under Hinduism. The temple is a place for Tirtha—pilgrimage. All the cosmic elements that create and celebrate life in Hindu pantheon, are present in a Hindu temple—from fire to water, from images of nature to deities, from the feminine to the masculine, from kama to artha, from the fleeting sounds and incense smells to Purusha—the eternal nothingness yet universality—is part of a Hindu temple architecture. The form and meanings of architectural elements in a Hindu temple are designed to function as the place where it is the link between man and the divine, to help his progress to spiritual knowledge and truth, his liberation it calls moksha.

The architectural principles of Hindu temples in India are described in Shilpa Shastras and Vastu Sastras.[4][5] The Hindu culture has encouraged aesthetic independence to its temple builders, and its architects have sometimes exercised considerable flexibility in creative expression by adopting other perfect geometries and mathematical principles in Mandir construction to express the Hindu way of life.[6]

The procedure for building a temple is extensively discussed, and it could be expressed in short as "Karshanadi Pratisthantam", meaning beginning with "Karshana" and ending with "Pratistha". The details of steps involved vary from one Agama to another, but broadly these are the steps in temple construction:

From the proportions of the inner sanctum to the motifs carved into the pillars, the traditional temple takes its first form on the master sthapati's drawing board. The architect initially determines the fundamental unit of measurement using a formula called ayadhi. This formula, which comes from Jyotisha, or Vedic astrology, uses the nakshatra (birth star) of the founder, the nakshatra of the village in which the temple is being erected matching the first syllable of the name of the village with the seed sounds mystically associated with each nakshatra and the nakshatra of the main Deity of the temple. This measurement, called danda, is the dimension of the inside of the sanctum and the distance between the pillars. The whole space of the temple is defined in multiples and fractions of this basic unit.

The Shastras are strict about the use of metals, such as iron in the temple structure because iron is mystically the crudest, most impure of metals. The presence of iron, sthapatis explain, could attract lower, impure forces. Only gold, silver, and copper are used in the structure, so that only the most sublime forces are invoked during the pujas. At especially significant stages in the temple construction (such as ground-breaking and placement of the sanctum door frame), pieces of gold, silver and copper, as well as precious gems, are ceremoniously embedded in small interstices between the stones, adding to the temple's inner-world magnetism. These elements are said to glow in the inner worlds and, like holy ash, are prominently visible to the Gods and Devas.

The ground plan is described as a symbolic, miniature representation of the cosmos. It is based on a strict grid made up of squares and equilateral triangles which are imbued with deep religious significance. To the priest-architect the square was an absolute and mystical form. The grid, usually of 64 or 81 squares, is in fact a mandala, a model of the cosmos, with each square belonging to a deity. The position of the squares is in accordance with the importance attached to each of the deities, with the square in the center representing the temple deity; the outer squares cover the gods of lower rank. Agamas say that the temple architecture is similar to a man sitting - and the idol in garbagriha is exactly the heart-plexus, gopuram as the crown etc.

The construction of the temple follows in three dimensional form exactly the pattern laid out by the mandala. The relationship between the underlying symbolic order and the actual physical appearance of the temple can best be understood by seeing it from above which was of course impossible for humans until quite recently.

Another important aspect of the design of the ground plan is that it is intended to lead from the temporal world to the eternal. The principal shrine should face the rising sun and so should have its entrance to the east. Movement towards the sanctuary, along the east-west axis and through a series of increasingly sacred spaces is of great importance and is reflected in the architecture. A typical temple consists of the following major elements

Vastu Shastra describes the inner sanctum and main tower as a human form, structurally conceived in human proportions based on the mystical number eight. According to Dr. V. Ganapati Sthapati, Senior Architect at the Vastu Government College of Architecture, the vibration of the space-consciousness, which is called time, is the creative element, since it is this vibratory force that causes the energetic space to turn into spatial forms. Therefore, time is said to be the primordial element for the creation of the entire universe and all its material forms. When these vibrations occur rhythmically, the resultant product will be an orderly spatial form. This rhythm of the time unit is traditionally called talam or layam.

Since every unit of time vibration produces a corresponding unit of space measure, vastu science derives that time is equal to space. This rhythm of time and space vibrations is quantified as eight and multiples of eight, the fundamental and universal unit of measure in the vastu silpa tradition. This theory carries over to the fundamental adi talam (eight beats) of classical Indian music and dance. Applying this in the creation of a human form, it is found that a human form is also composed of rhythmic spatial units. According to the Vastu Shastras, at the subtle level the human form is a structure of eight spatial units devoid of the minor parts like the hair, neck, kneecap and feet, each of which measures one-quarter of the basic measure of the body and, when added on to the body's eight units, increases the height of the total form to nine units. Traditionally these nine units are applied in making sculptures of Gods.

Since the subtle space within our body is part of universal space, it is logical to say that the talam of our inner space should be the same as that of the universe. But in reality, it is very rare to find this consonance between an individual's and the universal rhythm. When this consonance occurs, the person is in harmony with the Universal Being and enjoys spiritual strength, peace and bliss. Therefore, when designing a building according to vastu, the architect aims at creating a space that will elevate the vibration of the individual to resonate with the vibration of the built space, which in turn is in tune with universal space. Vastu architecture transmutes the individual rhythm of the indweller to the rhythm of the Universal Being.

The goal of a temple's design is to bring about the descent or manifestation of the unmanifest and unseen. The architect or sthapati begins by drafting a square. The square is considered to be a fundamental form. It presupposes the circle and results from it. Expanding energy shapes the circle from the center; it is established in the shape of the square. The circle and curve belong to life in its growth and movement. The square is the mark of order, the finality to the expanding life, life's form and the perfection beyond life and death. From the square all requisite forms can be derived: the triangle, hexagon, octagon, circle etc. The architect calls this square the vastu-purusha-mandala-vastu, the manifest, purusha, the Cosmic Being, and mandala.

The vastu-purusha-mandala represents the manifest form of the Cosmic Being; upon which the temple is built and in whom the temple rests. The temple is situated in Him, comes from Him, and is a manifestation of Him. The vastu-purusha-mandala is both the body of the Cosmic Being and a bodily device by which those who have the requisite knowledge attain the best results in temple building.

In order to establish the vastu-purusha-mandala on a construction site, it is first drafted on planning sheets and later drawn upon the earth at the actual building site. The drawing of the mandala upon the earth at the commencement of construction is a sacred rite. The rites and execution of the vastu-purusha-mandala sustain the temple in a manner similar to how the physical foundation supports the weight of the building.

Based on astrological calculations the border of the vastu-purusha-mandala is subdivided into thirty-two smaller squares called nakshatras. The number thirty-two geometrically results from a repeated division of the border of the single square. It denotes four times the eight positions in space: north, east, south, west, and their intermediate points. The closed polygon of thirty-two squares symbolizes the recurrent cycles of time as calculated by the movements of the moon. Each of the nakshatras is ruled over by a Deva, which extends its influence to the mandala. Outside the mandala lie the four directions, symbolic of the meeting of heaven and earth and also represent the ecliptic of the sun-east to west and its rotation to the northern and southern hemispheres.